Research

My research explores how biological systems learn, adapt, and make decisions through internal dynamics such as oscillations, feedback, and network interactions. I develop and analyze mathematical models using tools from dynamical systems, network theory, and agent-based approaches to study systems ranging from slime molds to brain organoids and to understand the principles of biological intelligence. In parallel, I’m interested in the philosophy of mathematical modeling and in how the scientific practice of mathematical biology shapes the kinds of questions we ask and the kinds of answers we allow.

Minimal cognition and learning across biological systems

I develop mathematical models to explore how simple biological systems—both neural and non-neural—can exhibit learning-like behavior through internal dynamics such as oscillations, feedback, and adaptation. This line of research aims to understand the fundamental mechanisms underlying cognitive behaviour, from slime molds to brain organoids.

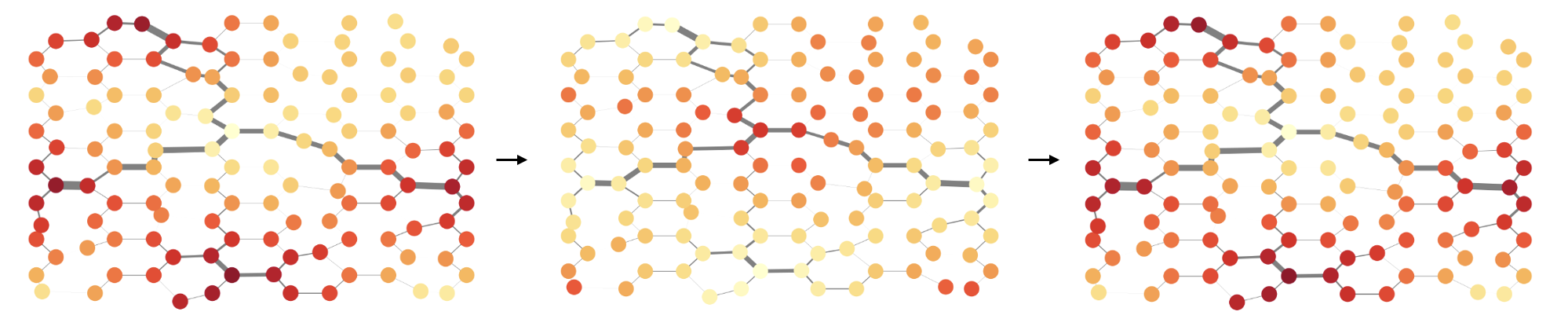

A minimal model of cognition based on oscillatory and current-based reinforcement processes

Building mathematical models of brains is difficult because of the sheer complexity of the problem. One potential approach is to start by identifying models of basal cognition, which give an abstract representation of a range organisms without central nervous systems, including fungi, slime moulds and bacteria. We propose one such model, demonstrating how a combination of oscillatory and current-based reinforcement processes can be used to couple resources in an efficient manner. We identify connections between our model and basal cognition in biological systems and slime moulds, in particular, showing how oscillatory and problem-solving properties of these systems are captured by our model.

Linnéa Gyllingberg, Yu Tian, David J.T. Sumpter, Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 2025 link

Non-neural pattern completion

In ongoing work, I’m developing a non-spiking, biologically inspired reservoir model that demonstrates pattern completion in non-neural systems. The system is inspired by Physarum polycephalum and uses adaptive weights and homeostatic regulation to anticipate periodic input patterns without a trained output layer.

This project is in collaboration with Polyphony Bruna.

Brain organoid dynamics

In a new collaboration, I’m beginning to explore how brain organoids might display learning-like behavior during development, and how this relates to underlying network dynamics.

Collective behavior and spatial modelling

Many biological systems display collective or spatially structured behaviour that emerges from local interactions and feedback. I use mathematical models to investigate how these interactions give rise to coordination, pattern formation, and decision-making across scales—from neural dynamics in fish shoals to ecological competition and growth.

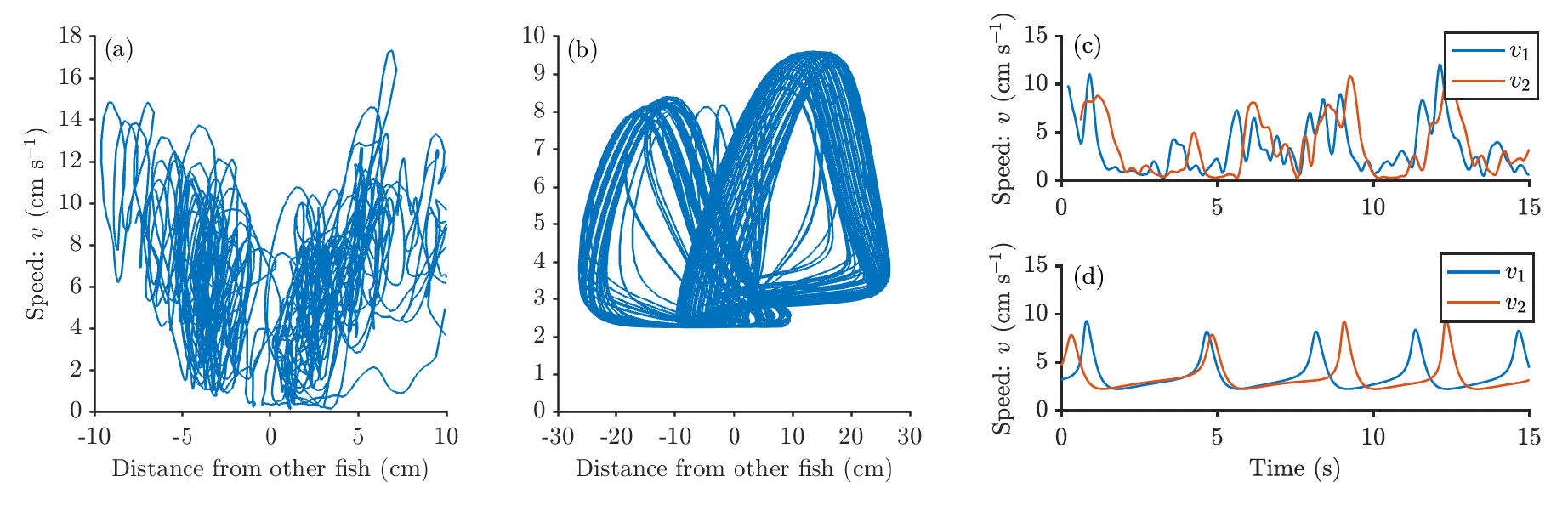

Using neuronal models to capture burst and glide motion and leadership in fish

While mathematical models, in particular self-propelled particle (SPP) models, capture many of the observed properties of large fish schools, they do not always capture the interactions of smaller shoals. Nor do these models tend to account for the observation that, when swimming alone or in smaller groups, many species of fish use intermittent locomotion, often referred to as burst and coast or burst and glide. We propose a model of social burst and glide motion by combining a well-studied model of neuronal dynamics, the FitzHugh-Nagumo model, with a model of fish motion.

Linnéa Gyllingberg, Alex Szorkovszky, David J.T. Sumpter

Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 2023

link

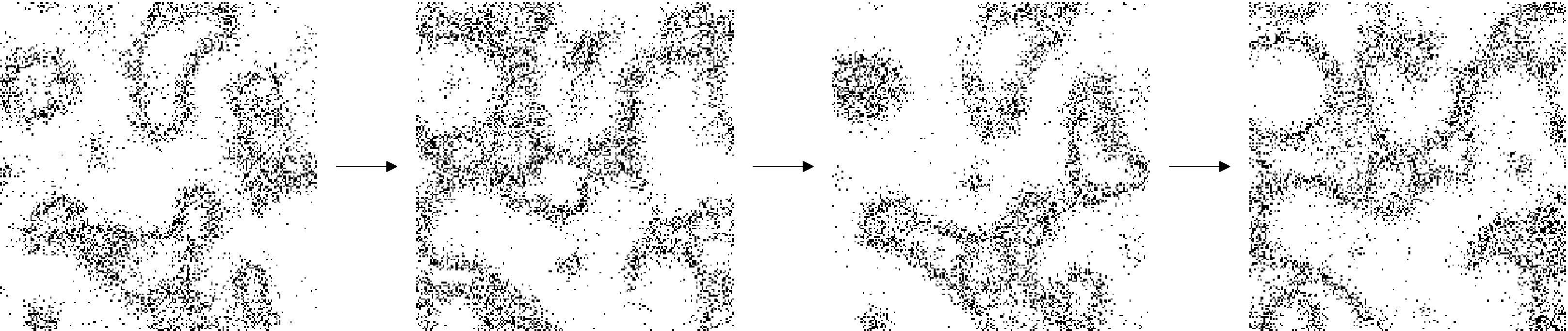

Finding analytical approximations for discrete, stochastic, individual-based models of ecology

We study an individual-based model of intra-specific interactions, inspired by the life cycle of many insects and microorganisms. We show that a mean-field approach is not enough to capture the complex spatial dynamics of ecological competition. Instead, we develop two approximations to capture this complexity: one based on coupling on a larger scale and one based on a very local scale.

Linnéa Gyllingberg, David J.T. Sumpter, Åke Brännström

Mathematical Biosciences, 2023

link

Philosophical aspects of mathematical modelling

Biological systems are complex systems. This statement is so often made, that it can obscure just how radical the consequences of complexity are for the life sciences. In the paper The Lost Art of Matheamatical Modelling we provide a critique of mathematical biology in light of rapid developments in modern machine learning. We argue that out of the three modelling activities — (1) formulating models; (2) analysing models; and (3) fitting or comparing models to data — inherent to mathematical biology, researchers currently focus too much on activity (2) at the cost of (1). This trend, we propose, can be reversed by realising that any given biological phenomena can be modelled in an infinite number of different ways, through the adoption of an open/pluralistic approach. We explain the open approach using fish locomotion as a case study and illustrate some of the pitfalls — universalism, creating models of models, etc. — that hinder mathematical biology. We then ask how we might rediscover a lost art: that of creative mathematical modelling.

Linnéa Gyllingberg, Abeba Birhane, David J.T. Sumpter, The Lost Art of Mathematical Modelling, Mathematical Biosciences, 2023.

link